Inside the Red

Cube: Rothko’s Seagram Paintings,

a case study of

obsessive practice.

Response to The

artist studio exhibition, Tate Modern 2018. (Visited 220318).

This

post considers: Practice through historical research - The role of

contextualising practice in the Laurentian Library and Rothko’s Seagram Mural

Project, practice through performance -

the staging of the ‘room’ with scaffolding to get the space right, practice

through communication - link with White Cube Thinking article, How to Exhibit

Practice? The Narrative continues, new stories about the paintings.

Continuing

from the post ‘White Cube Thinking’, Rothko

in his Seagram commission, was absorbed by and wanted to express the feeling of

being in (time, space, memory, time-based, Decartian body in space, in the Ingold

taskscape of the library) Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library (1525) – a Medici

quattrocento building next to il Duomo in Florence. This library was purpose

built for study, academia, grandeur and awe; it seems to me, built on the same

grand scale as the high alter by Bernini at the Vatican. The size of them

dwarfs the faithful by their giant proportions, just as the dimension of the

Seagram Mural is oversized, immersive is a word Rothko a Russian (now part of

Latvia) born American Painter from the Abstract expressionist movement.

The

whole idea of blocking up the windows, as O’ Doherty (2000) comments on the white

cube contemporary gallery space, is to create a rarefied atmosphere of the intelligencia,

academia and preservation. In this arena by which to communicate practice, natural

light is denied just as in the Laurentian Library, and this is one of the themes

Rothko was trying to portray in this series of paintings.

The Laurentian

Library is a veneration of the past, a cathedral to wealth and power in the form

of the written word and books (privileging type, expensive education and

literacy). Rothko’s paintings echo the emphasis of feeling, the Seagram

Building a Modernist Medici monument. This was a new American temple to

commerce, capitalism, new money, grand families, and idea of immortality. Interestingly

Rothko never completed the commission, he made the paintings and then changed

his mind and did not give them over to Seagram, Johnson or van de Rohe. Wonder what

happened? Instead they were donated to the Tate.

Sitting

in the Rothko room I am in a different white cube space, a deliberately ‘compact

and oppressive space’, the blurb on the wall reminds us (the wall which by the

way is cadmium yellow). The specific dimensions create a suffocating presence.

The original nine paintings on every wall in the room, huge in scale and dimension,

Rothko wanted the viewer to have an immersive experience. The reds and maroons

redolent of the Minoan palace of Knossos on Crete where the hot scarlet walls are

a backdrop for live and roiling botanical frescos coupled with acrobatic bull

dancers and bare chested snake grappling priestesses. Religious ecstasy, and a collision

with the sublime in a hypnagogic state, is this what Rothko was trying to

induce? Intriguing triangles of connection drawn in my head. Some with dotted

lines some with coloured lines, solid lines, intersecting connecting subjects

and images and place and thoughts. Some of them golden.

Paintings imaginatively named, Maroon on Black,

Red on Maroon, all executed in 1958-9.

On the cusp of post modernism, on the cusp of the decade, on the cusp of

prosperity in a post war era, American dominance globally, monetarily, was

paramount, the power had shifted from ‘old’ broken post war Europe to the New World

Order.

The

paintings in oxblood, maroon and blood red. Making the viewer feel, as the information

puts it ‘trapped’ – imprisoned by art, by the visual, arrested, calling the

colour ‘brick’ and using the phrase ‘bricked up’, “all they can do is butt their heads against

the wall forever” Rothko states, the muted lighting and closed eyelid red give

a feeling of being buried alive. The four Seasons restaurant in the 1950s Seagram

building on Park Avenue where the paintings were originally destined for, was

the antithesis of the white cube or the feeling of being ‘bricked up’. All

glass and light and plants, airy high ceilings, open plan booths.

Rothko

built a mock-up in scaffolding of the Four Seasons space in an unused school

gymnasium where he could simulate the proportions of the private dining area. I

like the idea that he was rehearsing the space like a dancer or an actor – working

in the foot print of the area specifying the context of his practice, he never

finalised the schema or fixed order for the paintings. The Seagram building, epitome

of modernism and technology, and advances of the 1950’s – the restaurant, the

Four Seasons making the outside inside and the inside outside (opposite to the

white cube which demands that all the art be inside and all the nature and

world outside – maybe even all the people on the outside). Here in this room,

in the Tate Modern the Rothko paintings are divorced from the restaurant that that

they were intended for but never actually reached.

Black on

maroon 1958; the shine on the surface or the blending of paint – ‘demanding

complete absorption’ but like the library – the blinds are not are not usually

the main attraction. Smells of boy-deodorant and perfumed college girls shuffling

past in this especially constructed space – specified by Rothko – has many

associations for me.

At age

of 18months I moved to Cliff Road with my parents, a new start from mums back

recovery, more room to move around in – or fill up. Inside the Victorian house once

owned by Atkinson Grimshaw, painted in the 1960s was this exact colour of

Rothko womb-blood colour. As a child the moving day was a big moment, wandering

in these vast spaces of the new house, empty as yet of furniture with the

overpowering and intense colour schemes, overpowering reds and maroons and

purples. The memory of the empty house filled with the immersive colourscapes

now are redolent of the Rothko gallery – the red cube.

Sitting

in the Seagram Mural room, this set of paintings became my child hood home, and transforms

again into a the Laurentian Library – stuffy – hot – stultifying atmosphere of

a library in the summer with bricked up windows. Learning practice – slow

crafting, and stillness, that is what libraries mean to me, hours sliding by.

In the library there is much to be felt, smelt, heard, seen and touched in this

place, it would be an interesting idea to re-curate these paintings in a local

library or even in the Laurentian library.

A recent play also re-curates Rothko and his paintings in a stage play by

John Logan (2009) called ‘Red’, it discusses the tension between commerce and creation.

The central action is around the creation of the Seagram Murals, the process

and decision making in the studio, in order to paint the abstract paintings. The

practice of being an artist.

Rothko’s

painting practice can be contextualised linking his 1958 Seagram Murals to a

Florentine Renaissance. He emulates the feeling of being in a library, the

windows closed and blinds pulled down against the sun. Each painting in the series

is a vertical or horizontal, soft edged rectangle, light diffusing from under

and round the edge of blinds creating dark silhouettes and tonally analogous

colours in a hot palate. The images

would not exist without this contextualisation, this research into a historical

building and all it may mean politically, psychologically and emotionally.

Rothko has a vision of the library room and decides to recreate the feeling of

space and memory so that the paintings are arranged like a stage set, echoing

the feeling of being in Florence at the Laurentian.

An interesting

addendum is the addition Vladimir Umanets gave to Black on Maroon 1958. In 2015

he casually went up to the painting on display in the Tate and wrote with black

ink in the corner of the painting. It said “A potential piece of yellowism.” Thinking

about narrativity, this act is now part of the story of the canvas. Paintings

even very abstract ones like the Seagram Murals have an implied narrative

content, the deep pools of red and maroon also invite the viewer to project something

of their own story onto the reflective, dream-like surface of the painting.

The

image also contains the memory and history of the artist, their intention, who

bought it, where was it hung, who was it passed to. During communist rule post

WW2 the people of Albania were not allowed to go to church, synagogue or Orthodox

Church. Whilst in Albania doing aid-work I met a man who had buried pictures

and statues from the Catholic Church under his house to avoid them being

destroyed, if he had been caught he would certainly have been arrested. These items

now replaced in the partially destroyed church have layers of narrative

attached to them. Just like the Rothko canvas, the Yellowism incident adds to

its value, adds to its public interest, and it is now a collaborative work. The

practice of a dead painter is responded to by a contemporary artist.

There is a

precedent for this kind of work, Robert Rauschenberg in 1953 bought a Willem De

Kooning drawing and rubbed it out with an eraser. Ai WeiWei bought ancient Chinese

vases and filmed himself smashing and destroying it or dunking it in candy

coloured paint. Unfortunately Umanets did not own the Rothko he was ‘collaborating’

on and so ended up with a two year prison sentence, which is another element of

the story of ‘Black on Maroon’ 1958.

O’Doherty, B., (2000) Inside

the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, Expanded Edition, London,

University of California Press.

exhibition seen

22/03/18, Curated by Helen Sainsbury

https://4wallsblg.wordpress.com/2015/01/14/restoring-the-graffitied-rothko-in-conversation-with-dr-bronwyn-ormsby-conservation-scientist-tate/,

Restoring the

Graffitied Rothko: In Conversation with Dr. Bronwyn Ormsby, Conservation

Scientist, Tate. JANUARY

14, 2015 ~ 4WALLSBLG,

accessed 24 March 2018.

Bernstien, F. A., 2013, Design Doyenne, WM Magazine, May 1,

2013 12:00 am

Keyes, B., (2015) EXPLORING THE TENSION BETWEEN COMMERCE AND

CREATION, ‘RED’ OPENS FRIDAY AT PORTLAND STAGE,

https://www.wmagazine.com/story/phyllis-lambert-seagram-building,

accessed 31 March 2018.

Maine Today online

magazine, Posted: March 25, 2015, http://mainetoday.com/theater/exploring-the-tension-between-commerce-and-creation-red-opens-friday-at-portland-stage/,

accessed 31 March 2018

Image: Rothko, untitled, section 2, 1959

Image: Laurentian Library Florence

Image: Ludwig Mies van der

Rohe and Phyllis Lambert with the model for the Seagram Building, New York,

1955.

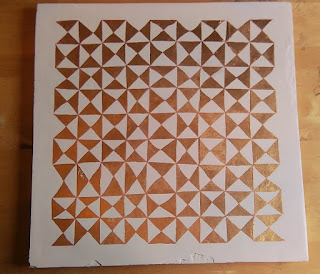

image: maquette by Rothko of possible hanging schema.

Image: Seagram Murals Tate Modern

Image: Four Seasons 1950's

Image: Black on Maroon, 1958

Image: Stage set from 'Red' play

Image: Rothko graffiti.

Comments

Post a Comment