Embodied knowledge, A Case

Study: Thinking Through Practice.

An artist and senior lecturer talks about her practice.

Susan is a sculptor and Director of Fine Art Studies at a Northern

University. What was formerly a college has recently earned university status.

All the lecturers as a result of the upgrade have had to alter the way they

think about their art practices and how they reflect on teaching practice and

where the two might intersect to benefit the institution, the students and the

individual.

This culture change has been a slow a difficult one. My FE

students are resistant to writing, which is the focus of my MPhil; possible

reasons are, they just want to make art, they don’t want to write or be asked

to think or spend time reflecting that could be spent making. Other reasons

could be a learning barrier such as dyslexia and being on the autism spectrum.

They are adults and may have dependents to care for and part time jobs that fit

around study.

Many artists think visually and are in tune with speaking and

listening rather than reading and writing. In the same way the

lecturing staff have also been resistant to research and have had negative

feelings towards what they presuppose it to entail, possibly because of some of

the same reasons as students, lack of time, pressure from work and family

commitments.

Facilitated by the very able Research Director Sophrosyne, this

transition has allowed staff to rethink and reimagine what research might be

for a lecturer who is at the same time an art and design practitioner.

Sophrosyne has expanded and augmented the definitions of what it means to be a

researcher and the kinds of activities that could be called research. For

instance one lecturer has used dance practice, one has used furniture making,

one has built a playpark in South Africa and many have had art exhibitions. All

these can be used as research if they are recorded, reflected on and have drawn

on academic philosophies and thought and brought it to bear on these diverse

projects.

Susan’s sculpture practice includes a writing practice and making,

she believes the studio is very important, and denotes the studio as small

holding where ideas through slow crafting have time and space to grow, as place

of experimentation where things may never get resolved and things are allowed

to fail in order to learn from them, it is the sanctity of ‘A Room of One’s

Own’ (2002) as advocated by Virginia Wolf in 1929. Denied entry to an oxford

library because she was a woman Wolf’s riposte was typically defiant, “Lock up

your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can

set upon the freedom of my mind.”

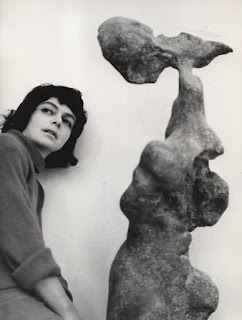

At a Local gallery Susan was

called upon to be an expert witness in the ‘lost’ sculptures of Alina

Szapocznikow. As the artist had passed away, information of the sculptures

construction was missing, her practice was not recorded.

Susan because of innate

understanding of the assembly and modelling of figures and heads from her own

education at art school, as she called it, her professor’s methods brought

forward and put into practice. Past pedagogy conflated with Susan’s

continued mastery of the ‘hand’(Sennett 2008 and Hyland 2018), her continued

practice, has a conception of how Szapocznikow’s cast and concrete

filled sculptures were made, calling it the artist’s ‘Psychological

fingerprint’.

Susan comprehends, through

appreciation of her own practice (also using complex multi piece moulds),

something a local theorists Ganymede had not understood when she had written a

paper on Alina Szapocznikow’s sculpture about the nature of making. Susan

was able to explain it to Ganymede through her embodied experience as a maker

sculptor her art practice together with reflection and research gave her the

understanding of the meaning of seam lines from the casting process.

All

establishments, universities and colleges and case study names have been

anonymised.

Gaffney, S., (2018) Seminar

on a life in Practice, for the MA in Creative Practice, Leeds Arts

University.

Hyland, T., (2017) Craft Working

and the “Hard Problem” of Vocational Education and Training. Open

Journal of Social Sciences, 5, 304-325. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2017.59021.

LSIS/SET/SUNCETT MPHIL Residential Conference, Seaburn Marriott, Feb 2018.

Sennett, R. (2008). The

Craftsman. London, Penguin

Hepworth (2017) 'Lost' sculpture

by Polish artist Alina Szapocznikow to be displayed in first UK retrospective, seen at: https://hepworthwakefield.org/news/lost-sculpture-by-polish-artist-alina-szapocznikow-to-be-displayed-in-first-uk-retrospective/

, accessed 3 March 2018

Wolf, V., (2002) A Room of One’s Own, London, Penguin.

(First written 1929).

Image: Alina Szapocznikow and

her sculpture 1960’s.

Comments

Post a Comment