The Story of the Handle Man:

Why practice based research?

As a student of ceramics in the 1980’s we had a

field trip around a pottery factory in Stoke on Trent. The ceramics industry

was in terminal decline, yet in Stoke, the majority of the jobs were in the potteries

and peripheral industries serving the factories. To such an extent that the whole

of Stoke had Potters Holiday in June, the whole place closed down. In this

factory we saw skilled mould makers, arcane jigger and jollying work making dishes,

expert engravers cutting copper plates to print willow pattern from, women whose

sole job was banding 24 ct gold on the rims of flatware.

What most fascinated me was the handle man. Standing

in front of an 8 foot rotating rack full of teacups, he unhinged a plaster mould,

popped out a dozen or so cast, green, handles and attached them to the teacups so precisely,

so neatly, so perfectly and so fast that after every twelve handles he gave himself

the treat of a cigarette, which he could

smoke at his ease as he had made up so much time. I think when Sennett (2008)

was talking about mastery, it was as part of a progression of states, and

although this handle man was a master at attaching the handle – that is all he

was master of. An isolated part of a larger whole that he never completed. Repetition

is only one part of mastery, as Sennett says after repetition, comes the

innovation, the divergence, the transcendency. Creating something never seen,

thought or touched before.

This accomplished handle man’s task became more

real to me a few years later when I took up the post of potter’s apprentice in

North Carolina. A five year journey of repetition, observation and emulation.

After completing my undergraduate studies, I thought I had a ‘handle’ on what

it was to be a potter, but I had no I idea.

Sennett (2008) says

that we need craft work as a way to keep ourselves rooted in material reality,

providing a steadying balance in a world which overrates mental facility.

(Hyland 2018) States that acting in and on the world brings

about knowledge and understanding; and the sharp divisions between knowing how

and knowing becomes redundant. The physical world cannot be separated from our

subjective conscious experience, through bodily sense perception.

As part of my job at Bob’s Village Pottery I was

tasked with attaching handles to many items such as casserole dishes, mixing

bowls, jugs and hundreds of thousands of mugs, steins and cups. Bob was the

master potter, he would throw two hundred and fifty mugs on a good day, and

after firming up overnight I would stand at the sink with a knife, a bowl of

water and a sponge and attach 250 handles. It would take the whole day and when

I first started it would take a day and a half. This is real acting on the

world, making something tangible and useful, after a while, the movements and

my body became a handle attaching machine, automatic of my thoughts and I was

free in my mind to drift and wander. As Merleau-Ponty (2013), put it I became the

embodied subject and as Bhor (1989) states, we construct the world by observing it.

In a very real way my construction of the mugs

allowed me time for reflection and connection, the clay, the water, my hands, the

action of attaching the handle. When else would I have a whole day to stand and

think, to contemplate the beauty of repetition? Of the very slight variations

in the mugs that made them hand thrown rather than slip-cast and factory made. The

satisfaction of making something good, whole, useful, not just one but

hundreds, lined upside-down on boards of 20, each completed board a great gratification,

weighing pounds, pleasing to heft the heavy board and enter the damp coolness

of the drying room. Hyland says that craft challenges the mind body dichotomy.

Good craft cannot be made without thinking and the design process being engaged

(Norton, 2012) divergence and innovation conflated with analysis, thinking

through more doing and rethinking. Practice based knowledge is striking in its multilayered complexity of philosophical thought.

Merleau-Ponty,

M (2013) Phenomenology of Perception, London

and New York, Routledge – Taylor and Francis Group.

Murdoch, D. R., (1989), Niels Bohr, N.,

(1989) Philosophy of Physics, New

Zealand, University of Caterbury.

Hyland, T., (2018) ETF, MPhil residential conference,

Sunderland University.

Norton, F., (2012) LSIS report, Access

All Areas, a research project on Curriculum development in FE, Access art

and design, published in the LSIS online Journal, University of Sunderland.

Sennett, R.

(2008). The Craftsman. London,

Penguin.

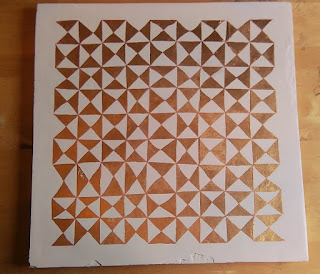

Image: Continuing on the Potter’s

Wheel with Iris Bedford Peterson, http://www.breckcreate.org/event/throwing-potters-wheel-iris-bedford-peterson-3/

accessed 26/02/18

Comments

Post a Comment