Practice

as Research; Thinking Through Theory

“Practice as

research not only produces knowledge that may be applied in multiple contexts,

but also has the capacity to promote a more profound understanding of how

knowledge is revealed, acquired and expressed.” (Barrett and Bolt, 2007).

Art practice, being a

craftsperson, a chef, a coder, a writer, a landscape gardener or equally a

teacher creates tacit knowledge, as Hyland, (2018) puts it, a thinking hand. Practice led research has the possibility to extend

understanding of the role of experiential, problem-based learning (Barrett and Bolt, 2003) and there is real potential

for situated knowledge and personally motivated understandings that could demonstrate how knowledge is revealed and acquired.

This

practice led research gives the participant when they reflected upon it, a

deeper way of knowing and an illumination of the winding path of understanding

of how it is that they know what they know, Barrett and Bolt (2007) believe it

is muscle memory that imputes a deeper understanding of practice. Further they

believe there is a diologic relationship between the exegesis, research and practice.

Inherent

practical wisdom reveals philosophical contexts for critical thinking about the

theoretical underpinning of art and design as advocated by Broadhead and

Gregson (2018) in their recent publication, Practical Wisdom

and Democratic Education. What is

practice – led and practice - based research in the context of pedagogy and

art-practice? The Australian academic art collective, Creative

Connections (2017) explains the distinction, commenting that, “If a creative

artefact is the basis of the contribution to knowledge, the research

is practice-based. If the

research leads primarily to new understandings about practice, it is

practice-led.” And so the two

terms have an apparent difference and are not so interchangeable.

“…the innovative and critical potential of

practice-based research lies in its capacity to generate personally situated

knowledge” (Barrett and Bolt 2007) personally situated knowledge adds authenticity to research, as Lorraine Leeson (2017) concurs in her book Art: Process: Change, written from a

very practical point of view, critical thinking in her opinion can only happen

in situated practice and practice based research.

In practice led learning students participate in their own education,

collaborate with each other facilitated by the teacher. Developing critical thinking through practice based research with students often

in my experience addresses issues of equality diversity and inclusion, it asks

learners and lecturers to actively engage (as hooks 2007 recommends), in the

class room in order to speak to the questions of race, gender and class through the practice of teaching and the lens of

criticality.

The situated and

personally motivated nature of knowledge acquisition through practice led

approaches presents an alternative to traditional pedagogies that emphasise

more passive modes of learning. Traditionally the teacher stands at the front

and expounds while the students go to sleep. Barrett and Bolt’s, (2007) anxiety over the normalisation of the

passive classroom is echoed by

Ken Brown (1998) who ruminates that all this thinking

about thinking provides an impetus for the introduction of programmatic methods

for remedying passive, rote learning which may well prove self-defeating.

An art education is the anathema of rote

learning, although some rote-ism of course is present, how can students be

original, daring, innovative when they don’t know what the cannon is in terms

of historical art movements and contemporary art practices. Although Marionetti

and his fellow Italian Futurists would disagree, berating history with his Futurist Manifesto of 1909, advocating

the destruction of the past, the burning of all ‘old’ paintings and books in

favour of the ‘Modern’. This to our contemporary ears has more than a touch of

the Zealot and the Radical about it which we cannot condone, but Marionetti’s

fervour is as he sees it a heroic push into the now, not being clouded or

tainted by the past. His art practice was

to live completely in the moment without repetition or emulation.

Brown (1998) believes early years learning should

be all about repetitive memorizing so the students have a foundation from which

to start to think critically and this also could have some truth to it. Art

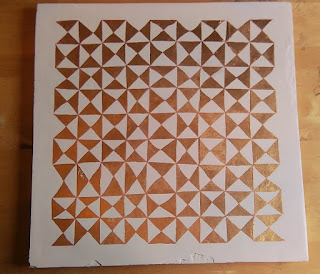

practice I believe has to start with emulation and repetition. As a designer-crafts woman this is how I began my education at art school, find a designer

you love they told us and make a piece of ceramics using the same techniques, using the

same glazes, using the same structural design. When I found one satisfying element in a piece of pottery, then I was asked to take that aspect and remake

the pot, make it severally and with variations until all the elements of the

pot were balanced, harmonious and pleasing to the eye and the hand.

As Sennett says in his book The Craftsman (2008) the path to mastery has stages, and right at

the beginning is observation, watching, researching, reading, looking, absorbing;

Next have a go, imitate, emulate, seek, mirror, echo; after that is the

practice, repetition, repeat 10000 times to become proficient, rehearse, study,

train; and finally transcendence, become your own person, have your own

thoughts, ideas, designs, to innovate. However none of this can happen without

the beginning part of observation and practice. This idea is upheld by Oakeshotte

(1933) who see that a long period of initiation, gives students the time and

space to learn to speak before they have anything significant to say he calls

this ‘learning without understanding’. To my mind no learning can occur without

some understanding, like a seed in the earth waits through the long winter and

bitter cold spring and all seems hopeless, lost, nothing happening, then one

warm day a shoot appears like a miracle. This is the kind of slow learning and slow crafting Sennett

and Hyland comprehend and perceive as the most fruitful way to becoming a

master of your particular practice. Tacit thinking – thinking with the hands, the thinking hand – thinking

by doing, debating, writing, speaking and listening – getting what is in a student

or a teacher’s head out of the interior castle and into the classroom.

Barrett, E., and Bolt,

B., Eds., (2007) Practice as Research

Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, London, I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Broadhead, S., and Gregson, M.,

(2018) Practical Wisdom and Democratic

Education: Phronesis, Art and Non-traditional Students, Cham, Switzerland, Palgrave

Macmillan.

Leeson, L., (2017) Art: Process:

Change. Inside a Socially Situated Practice, Routledge series; Advances in

Art and Visual Studies, New York, Routledge

Brown, K., (1998) Education Culture and Critical Thinking, Aldershot,

Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

hooks, b., (2007) Teaching

Critical Thinking, Practical Wisdom, New York, Routledge.

Hyland, T., (2018) ETF, MPhil residential conference,

Sunderland Univeristy

Oakeshott, M., (1933) Experience and its Modes, London, Cambridge.

Sennett, R. (2008). The Craftsman. London, Penguin

The difference between

practice based and practice led research

<https://www.creativityandcognition.com/research/practice-based-research/differences-between-practice-based-and-practice-led-research/>

accessed 23/09/17.

(2009),

Words in Freedom, Futurism at 100; Museum of Modern Art, New York,

https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2009/futurism/ accessed 27 February 2018.

Comments

Post a Comment