Measurability

and The story of the man who smiled

The story I want to tell you about a craft class I

taught in a local Care Home where we would engage one morning a week with sessions

on sewing, drawing, pastels, still life, working from memory photos from the

1930’s and 40’s, and even paper making. It was a shifting population and

residents moved in for assessment and out back home or into residential care. All

the projects had to be completed in one lesson. Some students I had every week.

One old gentleman in particular, very nicely turned

out but who never spoke and often looked depressed and sad. And he would need huge

amounts of encouragement to attempt the crafts each week. Always crumpled his work up and threw it in

the bin at the end of each session.

One week I had decided to do a Georges Braques

(1882-1963) themed still life and being a fiddle player, I have a violin which

I brought in and set up with some sheet music and a music stand in a still life

arrangement. When this man came in – he looked at what we were doing that day,

took a seat right next to the still life and smiled.

No one could tell me how wonderful this was, how

ground breaking, how much movement that one smile demonstrated and showed.

Perhaps I could have measured it with a ruler. Because measurement was

meaningless in this case, funding and therefore learning was demonstrated by

the evidence of a smile. It made my day and he sat down and made a wonderful

drawing, and with a very few words let us know that he had played the violin

and that he was very pleased to see his old musical friend again.

Measuring distance travelled in terms of learning

is not an easy task, tick boxes only go so far, recapping only goes so far.

Matthew Lipan in his book, Thinking in

Education (2003) says that educational measurements are …’not precise,

clear cut and technical; instead they are rather diffuse and contestable’.

The change theory ideas from (Mitchell, De Lange, Moletsane, 2017)

describe how in participatory research a ‘theory of change’ is very important,

it assists the researcher (me) and the participants (in this case elderly

members of a care home craft club) to describe and analyse issues in a user

friendly non formal way, affecting our class

and so effect change. For instance did they want more memory prompts, more ‘hands

on’ activities, more props with which to start conversations and connections to

the past?

How to describe change? For me this is a question

I ask myself, I want to change and become a better teacher and I want to subtly

alter the curriculum for my current FE students to include the elusive Critical

Thinking that can’t be tracked, monitored, measured in litmus paper used on it.

A single conversation can demonstrate change, a phrase in a diary can demonstrate

a shift in thought brought on by the tantalizing, informative, moving feast of

critical thinking.

Like the man who smiled – through props and mnemonic

associations with the violin I was able to begin to understand the context of

where a student had come from. Find this out through their stories through narrative

inquiry. As a consequence of his story I understand his past in relation to his

present which is part of his education journey story. His smile was an

acknowledgement, an affirmation, a semiotic sign of progress made, connections

reached, an acceptance of the possibility of agency within his own narrative,

even if it is just in his head (being restricted by age and infirmity).

Lipman, M., (2003) Thinking in Education, 2nd

edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, C., De Lange, N., Moletsane, R., (2017) Participatory Visual Methodologies, Social

Change and Policy, London, Sage Publications Inc.

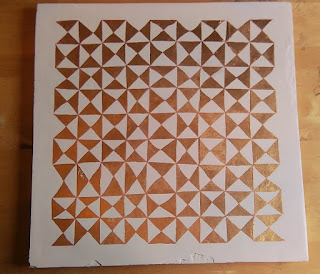

Image: Georges Braques, Man With a Violin, 1912.

Comments

Post a Comment