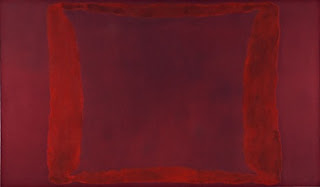

Inside the Red Cube: Rothko’s Seagram Paintings, a case study of obsessive practice. Response to The artist studio exhibition, Tate Modern 2018. (Visited 220318). This post considers: Practice through historical research - The role of contextualising practice in the Laurentian Library and Rothko’s Seagram Mural Project, practice through performance - the staging of the ‘room’ with scaffolding to get the space right, practice through communication - link with White Cube Thinking article, How to Exhibit Practice? The Narrative continues, new stories about the paintings. Continuing from the post ‘ White Cube Thinking ’ , Rothko in his Seagram commission, was absorbed by and wanted to express the feeling of being in (time, space, memory, time-based, Decartian body in space, in the Ingold taskscape of the library) Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library (1525) – a Medici quattrocento building next to il Duomo in Florence. This library was purpose built for study, acad...